Planting the future

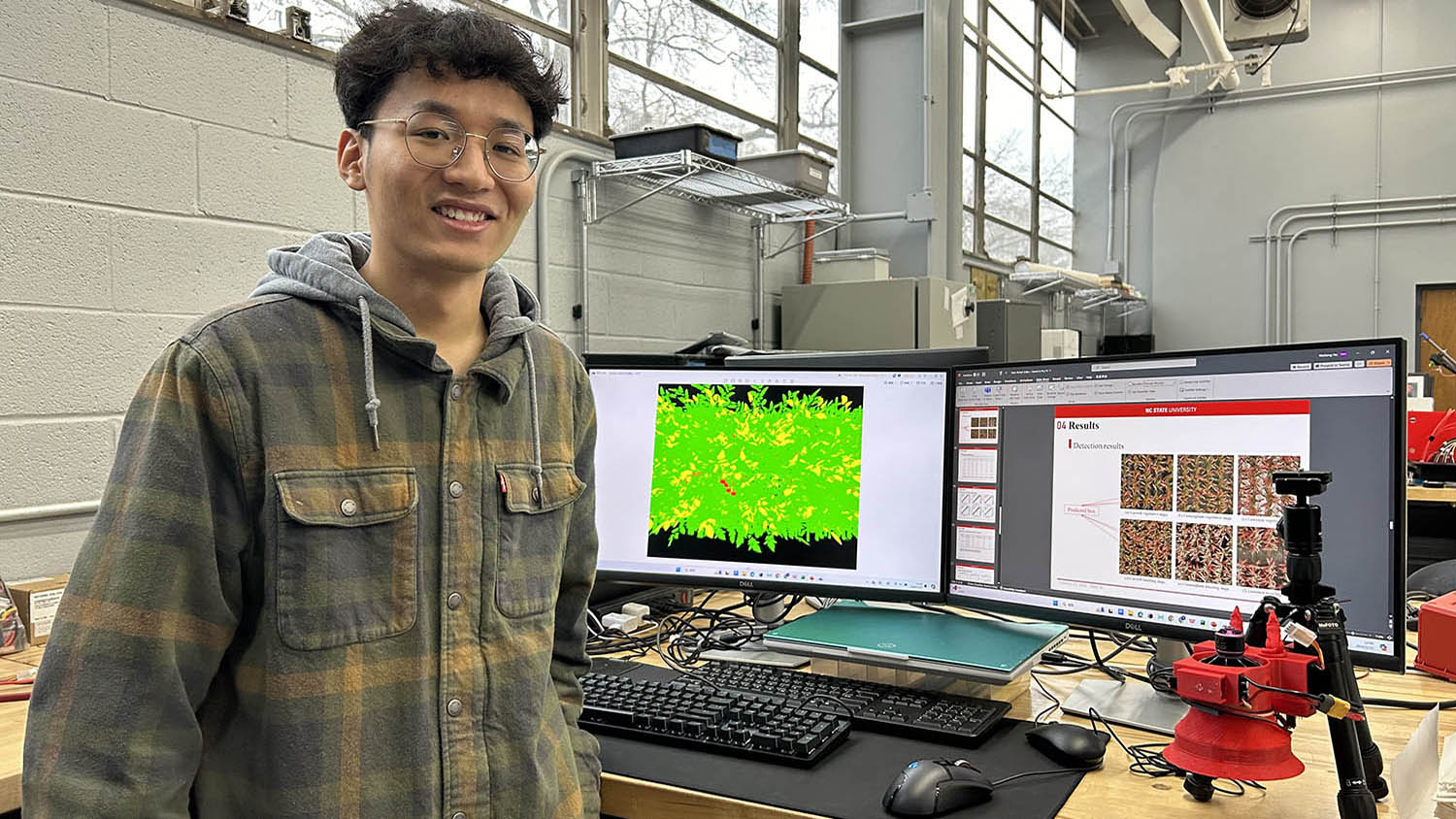

With support from the Trolinder graduate student endowment, Weilong He is aiming to make plant science high tech.

Tracking crop health and growth is time consuming on a good day. Traditionally, plant breeders have to plod through densely packed rows on foot to manually measure and observe the size, quality and angle of every leaf.

This tedious work can come at an even greater cost if breeders and farmers can’t identify problems fast enough to ensure the best yield from their crops.

But NC State University graduate student Weilong He is focused on creating high-tech solutions that can help breeders save time and identify problems faster so they can address them sooner. As a graduate research assistant in the Robotics and Automation Lab in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, He has spent his first year at NC State exploring how to use machine learning algorithms in tandem with drone images to assess crop leaves.

“I love the process of solving a problem,” says He, who earned his undergraduate degree in electronic information technology. “I like that you work on the problem many times and try almost every solution until you find the best way to solve the problem.”

Related: Meet the four recipients of the first graduate student endowment for N.C. PSI.

Part of the inaugural cohort of the Norma L. Trolinder N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative Graduate Student Endowment Award, He, who is pursuing his Ph.D. in agricultural engineering, feels his work is the next chapter of research of endowment benefactors Norma and Linda Trolinder. The mother-daughter duo co-founded South Plains Biotechnologies Inc. in the 1990s and focused their work on plant genetics and providing research services to agricultural companies. Linda Trolinder went on to hold research and development roles with companies such as Bayer CropScience and BASF.

“The Trolinder award has enabled me to devote more time and resources to my research in plant sciences,” says He. “It has facilitated my participation in academic conferences and field trips, providing invaluable opportunities to engage with esteemed scholars in plant science, which has significantly enriched my understanding and contributed to the progress of my research endeavors.”

That support is empowering He to explore the future of plant science.

“In 2024, technology is the next step in the plant sciences,” says He. “We strive to know how we can use these developments to create algorithms to support the plant sciences area.”

One of those areas He is working on is how to better automate the process of measuring the angles of corn leaves. Breeding specialists currently have to do it by hand, which can take many man- hours to complete. The angle of maize leaves is important for determining the light and water interception within the tightly packed rows of crops.

To save breeders time, He is working on developing a machine learning algorithm that can generate measurements for every maize leaf based on drone images of a corn field. The technology, so far, is promising with more than 90% accuracy.

Related: Learn more about Norma and Linda Trolinder.

Another project centers on developing an algorithm that can identify healthy, diseased and withered leaves on tomato plants. The long-term goal, says He, is to have the algorithm correctly label the health of the leaves and then eventually predict the health of the plant.

He also spent time last summer putting his electronic engineering skills to work for Lina Quesada-Ocampo, professor of plant pathology. For that project He helped build a remote controlled spore trap system that can efficiently collect spores from cucumber fields in order to predict the arrival of spore diseases, and ultimately provide farmers with advance warning and advice on how to control a potential outbreak.

He says the best part of his work as a student in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences is blending his love of the technical world with that of the natural world.

“I chose to do research in agriculture because I really like plants,” says He. “From a very small age, I planted a lot of flowers and other plants in my own garden. So, when I graduated with my bachelor’s degree, I wanted to do research about plants. Now, I’ve combined my love of electronic and computer engineering with agriculture.”

This post was originally published in College of Agriculture and Life Sciences News.