Robotic prosthetic ankles that are controlled by nerve impulses allow amputees to move more “naturally,” improving their stability, according to a new study from North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“This work focused on ‘postural control,’ which is surprisingly complicated,” says Helen Huang, corresponding author of the study and the Jackson Family Distinguished Professor in the Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at NC State and UNC.

“Basically, when we are standing still, our bodies are constantly making adjustments in order to keep us stable. For example, if someone bumps into us when we are standing in line, our legs make a wide range of movements that we are not even necessarily aware of in order to keep us upright. We work with people who have lower limb amputations, and they tell us that achieving this sort of stability with prosthetic devices is a significant challenge. And this study demonstrates that robotic prosthetic ankles which are controlled using electromyographic (EMG) signals are exceptionally good at allowing users to achieve this natural stability.” EMG signals are the electrical signals recorded from an individual’s muscles.

The new study builds on previous work, which demonstrated that neural control of a powered prosthetic ankle can restore a range of abilities, including standing on challenging surfaces and squatting.

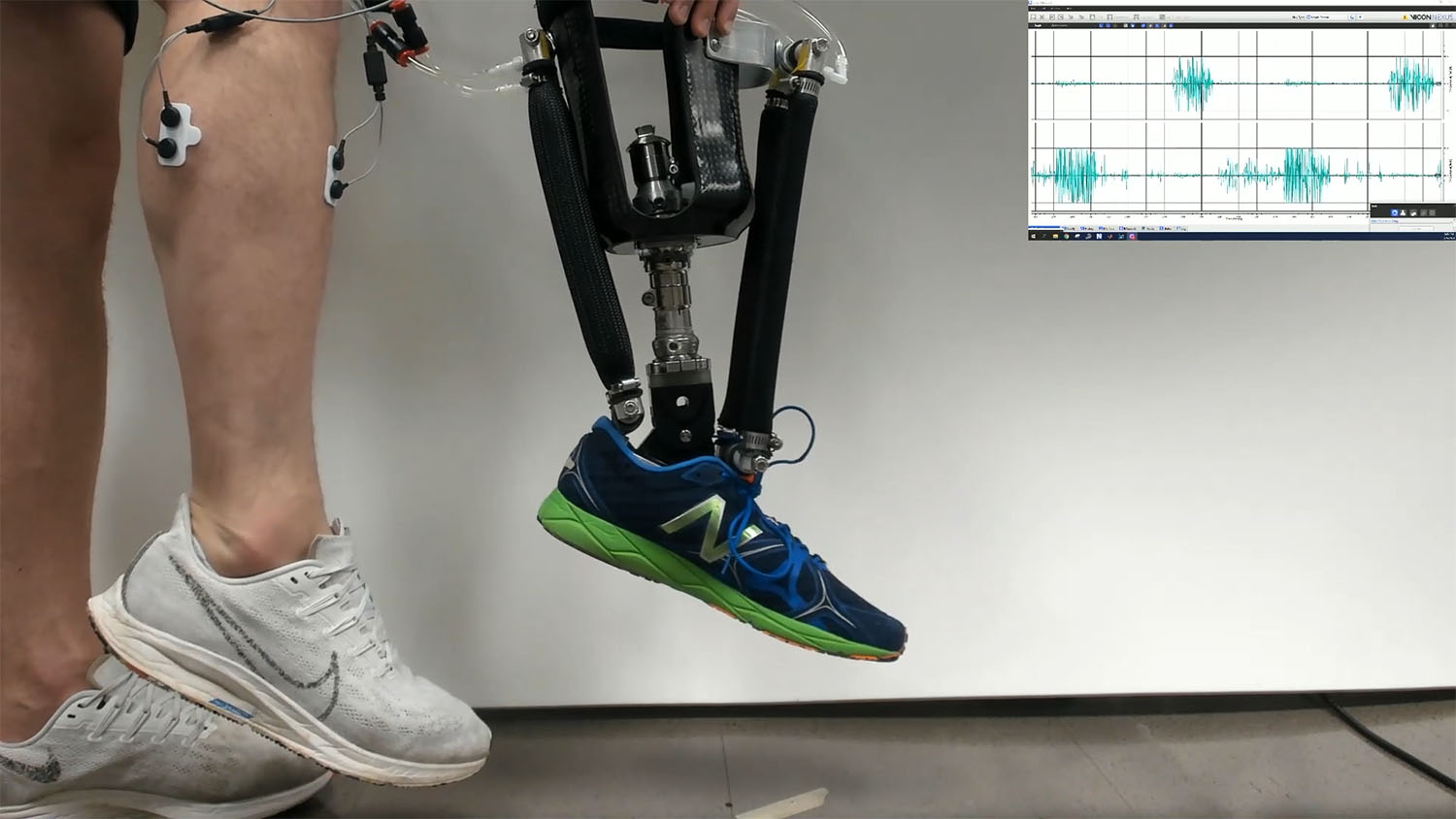

For this study, the researchers worked with five people who had amputations below the knee on one leg. Study participants were fitted with a prototype robotic prosthetic ankle that responds to EMG signals that are picked up by sensors on the leg.

“Basically, the sensors are placed over the muscles at the site of the amputation,” says Aaron Fleming, co-author of the study and recent Ph.D. graduate from NC State. “When a study participant thinks about moving the amputated limb, this sends electrical signals through the residual muscle in the lower limb. The sensors pick these signals up through the skin and translate those signals into commands for the prosthetic device.”

The researchers conducted general training for study participants using the prototype device, so that they were somewhat familiar with the technology.

Study participants were then tasked with responding to an “expected perturbation,” meaning they had to respond to something that might throw off their balance. In everyday life, this could be something like catching a ball or picking up your groceries. However, in order to replicate the conditions precisely over the course of the study, the researchers developed a mechanical system designed to challenge the stability of participants.

Study participants were asked to respond to the expected perturbation under two conditions: using the prosthetic devices they normally used; and using the robotic prosthetic prototype.

“We found that study participants were significantly more stable when using the robotic prototype,” Fleming says. “They were less likely to stumble or fall.”

“Specifically, the robotic prototype allowed study participants to change their postural control strategy,” says Huang. “For people who have their intact lower limb, postural stability starts at the ankle. For people who have lost their lower limb, they normally have to compensate for lacking control of the ankle. We found that using the robotic ankle that responds to EMG signals allows users to return to their instinctive response for maintaining stability.”

In a separate portion of the study, researchers asked study participants to sway back and forth while using their normal prosthetic and while using the prototype robotic prosthetic. Study participants were equipped with sensors designed to measure muscle activity across the entire lower body.

“We found that muscle activity patterns in the lower body were very different when people used the two different prostheses,” Huang says. “Basically, muscle activation patterns when using the prototype prosthetic were very similar to the patterns we see in people who have full use of two intact lower limbs. That tells us that the prototype we developed mimics the body’s behavior closely enough to allow people’s ‘normal’ neural patterns to return. This is important, because it suggests that the technology will be somewhat intuitive for users.

“We think this is a clinically significant finding, because postural stability is an important issue for people who use prosthetic devices. We’re now conducting a larger trial with more people to both demonstrate the effects of the technology and identify which individuals may benefit most.”

A paper on the study, “Neural Prosthesis Control Restores Near-Normative Neuromechanics in Standing Postural Control,” is published in the journal Science Robotics. The paper was co-authored by Wentao Liu, a Ph.D. student in the Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering. The work was done with support from the National Institutes of Health, under grants F31HD101285 and R01HD110519; and from the National Science Foundation, under grant 1954587.

-shipman-

Note to Editors: The study abstract follows.

“Neural Prosthesis Control Restores Near-Normative Neuromechanics in Standing Postural Control”

Authors: Aaron Fleming, Wentao Liu and He (Helen) Huang, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, North Carolina State University and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Published: Oct. 18, Science Robotics

Abstract: Current lower-limb prostheses do not provide active assistance in postural control tasks to maintain the user’s balance, particularly in situations of perturbation. In this study, we aimed to address this missing function by enabling neural control of robotic lower limb prostheses. Specifically, electromyographic (EMG) signals (amplified neural control signals) recorded from antagonistic residual ankle muscles were used to drive a robotic prosthetic ankle directly and continuously. Participants with transtibial amputation were recruited and trained in using the EMG-driven robotic ankle. We studied how using the EMG controlled ankle affected the participants’ anticipatory and compensatory postural control strategies and stability under expected perturbations, compared to when using their daily passive devices. We investigated the similarity of neuromuscular coordination (by analyzing motor modules) of the participants, using either device in a postural sway task, to that of able-bodied controls. Results showed, compared to their passive prosthesis, the EMG-controlled prosthesis enabled participants to employ near normative postural control strategies evidenced by improved between-limb symmetry in intact-prosthetic center-of-pressure and joint angle excursions. Participants significantly improved postural stability evidenced by a reduction in steps or falls using the EMG-controlled prosthetic ankle. Furthermore, after relearning to use residual ankle muscles to drive the robotic ankle in postural control, nearly all participants’ motor module structure shifted towards that observed in individuals without limb amputations. Here we have demonstrated the potential benefit of direct EMG control of robotic lower limb prostheses to restore normative postural control strategies (both neural and biomechanical) toward enhancing standing postural stability in amputee users.

This post was originally published in NC State News.

- Categories: