Fog alert

CCEE researchers lead the way on fats, oils and grease problem

On the surface, it might seem harmless enough: hot fats, oils and grease from cooking are poured down the drain in liquid form and disappear just as water does, right?

On the surface, it might seem harmless enough: hot fats, oils and grease from cooking are poured down the drain in liquid form and disappear just as water does, right?

Wrong, say three researchers in the Department of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering (CCEE).

Fats, oils and grease (often shortened to FOG) become hardened deposits in pipes and sewer systems. Even worse, they can trap non-biodegradable solids, such as wet wipes, creating a mass over time that can cause backups and spills.

These so-called “fatbergs” have made headlines in recent years. In 2013, a fatberg weighing roughly 17 tons was discovered in drains under a road in London. In 2017, one discovered under the streets of Baltimore caused a sewage spill totaling 1.2 million gallons.

“Because of the revitalization of cities, this problem is getting worse as urban environments grow,” said Dr. Joel Ducoste, professor in CCEE and assistant dean of graduate student advancement and faculty enrichment in the College. “It’s a problem that will only grow unless people stay on top of it.”

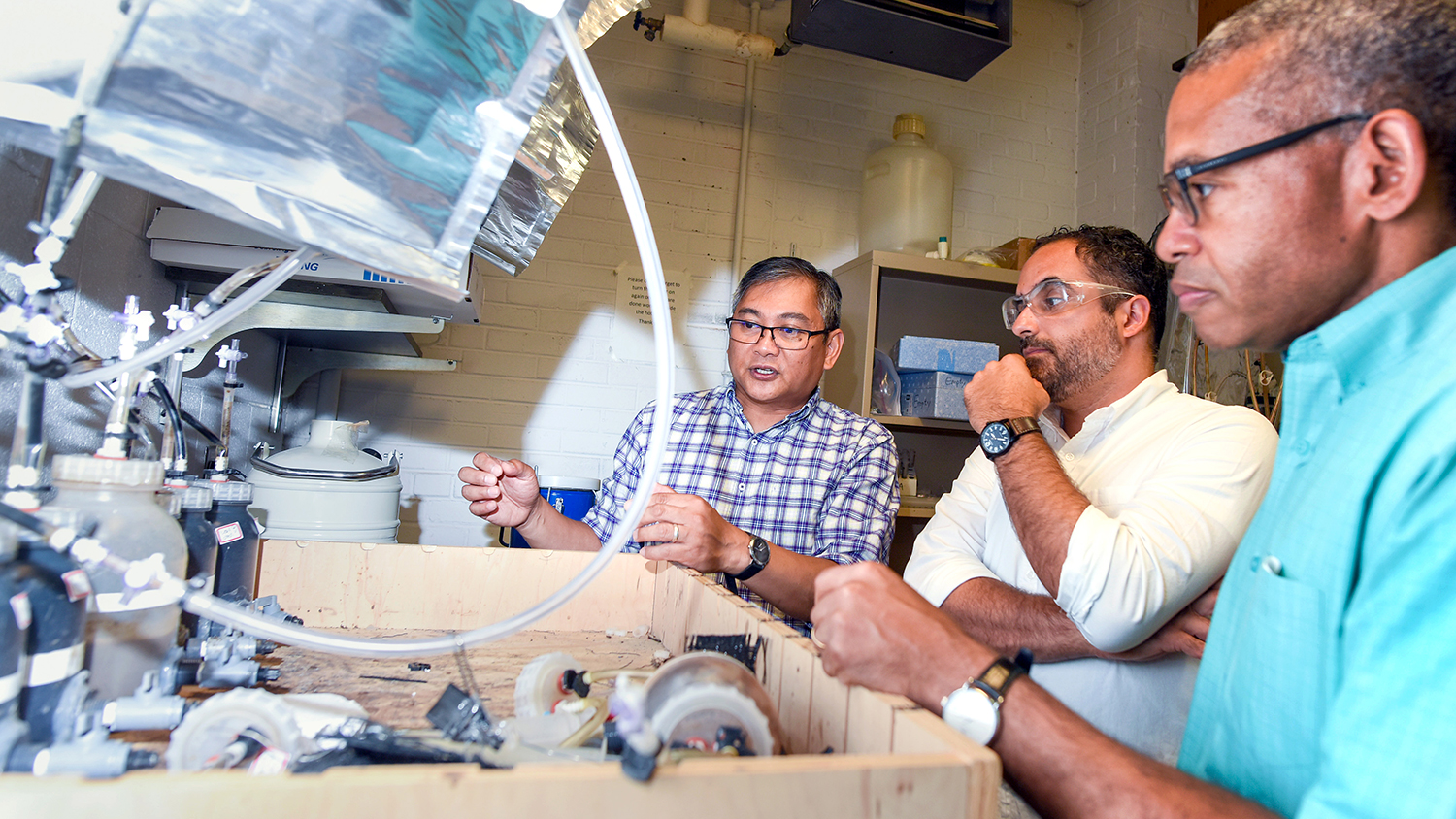

It’s been more than a decade since CCEE’s Ducoste; Dr. Francis de los Reyes, III, professor and University Faculty Scholar; and Dr. Tarek Aziz, assistant professor and coordinator of undergraduate advising, began researching this topic of what they call an often under-recognized pollutant.

It began when an employee of the nearby town of Cary, NC, approached the researchers. The town was seeing problems with its sewer lines related to fat cells and grease, and couldn’t get academics to pay attention to the issue, Ducoste said.

“We started looking at it and found there was not much research out there,” he said.

The group began investigating and in the years since, has performed comprehensive research on everything from potential ways to stop FOG from getting into the collection system, to processes that can be used to treat and remove existing FOG blockages and damage, and whether there are benefits to be had from these pollutants — even proving they can instead be converted to energy.

The System

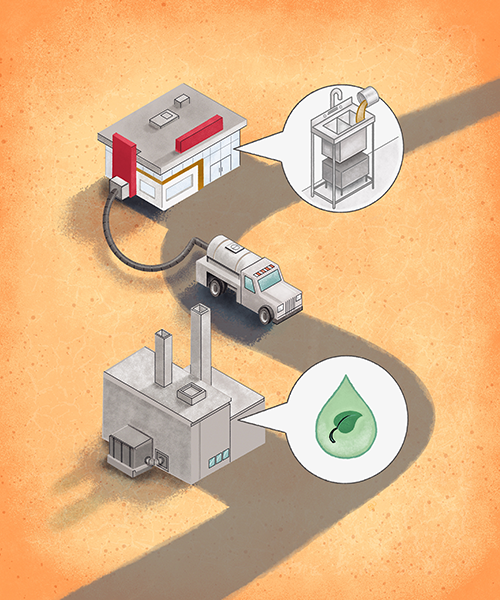

The food service industry produces the largest amounts of FOG, thus urban areas tend to see the brunt of the problems, however, suburban areas are not immune, the researchers say. From the time fats, oils and grease leave the stove, there are a number of mechanisms in place to keep FOG out of the sewers, but they don’t always work perfectly, de los Reyes said.

In the food service industry, there’s often a grease trap to catch FOG as it goes down the drain, or a larger tank underground called a grease interceptor, which serves as the last line of defense before the sewer line, he said. Usually, trucks extract the FOG from these interceptors and haul it away, but FOG and fatty acids still get through into the sewer pipes.

There’s also the issue of what to do with the substance when trucks do haul it away, Aziz said. For example, they found it is sometimes driven to a rural area and sprayed back out onto the land. That information led the three to begin exploring whether biology could be used to convert FOG into fuel.

Far-Reaching Research and Results

Research reached across the sciences, from chemistry to physics to biology. Among their projects, the three examined the biology of FOG and whether there are microbial ways to break it down. They’ve looked at the concept of anaerobic co-digestion and whether methane, a gas that can be used for energy, could be created from the pollutants. It turns out it can, which presents the possibility of using this “pollutant” as a biofuel, Aziz said.

They’ve researched structural changes as well — whether there are ways to stop grease from flowing through the grease traps and grease interceptors — as well as ways to “clean” the FOG from the pipes to which it can adhere.

For years, the three have been leaders in this area of research. Fatbergs prompted some research in the United Kingdom and other locations, however, Ducoste said those research projects have traditionally been smaller and more specialized.

“NC State has been the primary bearer of what’s going on,” he said. “We’ve set the tone as far as challenges, potential solutions and energy use strategies.”

Drawing from their research, the three faculty members are focused on three pillars of change: improving education, educating food service workers about the problem; changes to technology, such as improvements to grease interceptors; and more vigilant attention paid to the maintenance of sewer pipes.

The three continue to offer education and training, often receiving requests to educate the engineers who are out there dealing with the issue. Today, they serve as advisors to town and city officials, receiving calls from all over the United States.

Working Together Yields Greater Results

Collaboration has been the key to success, the three say. While there has been empirical and anecdotal information over the years that explains what leads to FOG deposits, or states that additives will make the problem go away, the NC State researchers are focused on the science of the problem. They say they’re asking the questions that will help understand how FOG behaves so that the engineering can be improved in the future.

Rather than one research project, the three have approached the issue as one phenomenon around which there are many aspects, de los Reyes said.

“This research speaks to the power of collaboration that NC State does well,” Ducoste said. “It builds off the idea that a complex solution requires multi-disciplinary thinking.”

Return to contents or download the Fall/Winter 2019 NC State Engineering magazine (PDF, 2.3MB).

- Categories: