Pig model to help research on human knee growth, injury treatment

To learn more about the human knee, biomedical researchers from NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill looked to pigs’ knees. Their work on how the knees of pigs compare to human knees at various stages of maturity will advance research by this group and others on injury treatment in young people.

“There’s a lot we still don’t know about how human knees work at different stages of maturity,” says Dr. Matthew Fisher, corresponding author of a paper on the research.

“What we’ve developed is a model that will allow us — or any research team — to study changes in the knee joint using pig knees,” says Fisher, who is an assistant professor in the UNC/NC State Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME).

“Our ultimate goal is to improve clinical treatment of joint injuries in children and teens, given the increased participation in sports and rise of injuries, such as to the anterior cruciate ligament or ACL,” Fisher says. “We’re specifically focused on changes that take place during the growth process — such as changes in the placement and orientation of ligaments during growth.”

Previous research had established that adult pig knees serve as a good model for research into adult human knees. However, less was known about how comparable pig and human knees were at various stages of growth.

For this study, researchers examined pig knees at six stages of growth, between birth and 18 months — which is comparable to early adulthood in humans. The researchers then compared the growth stages found in pigs to the available data on human knee growth.

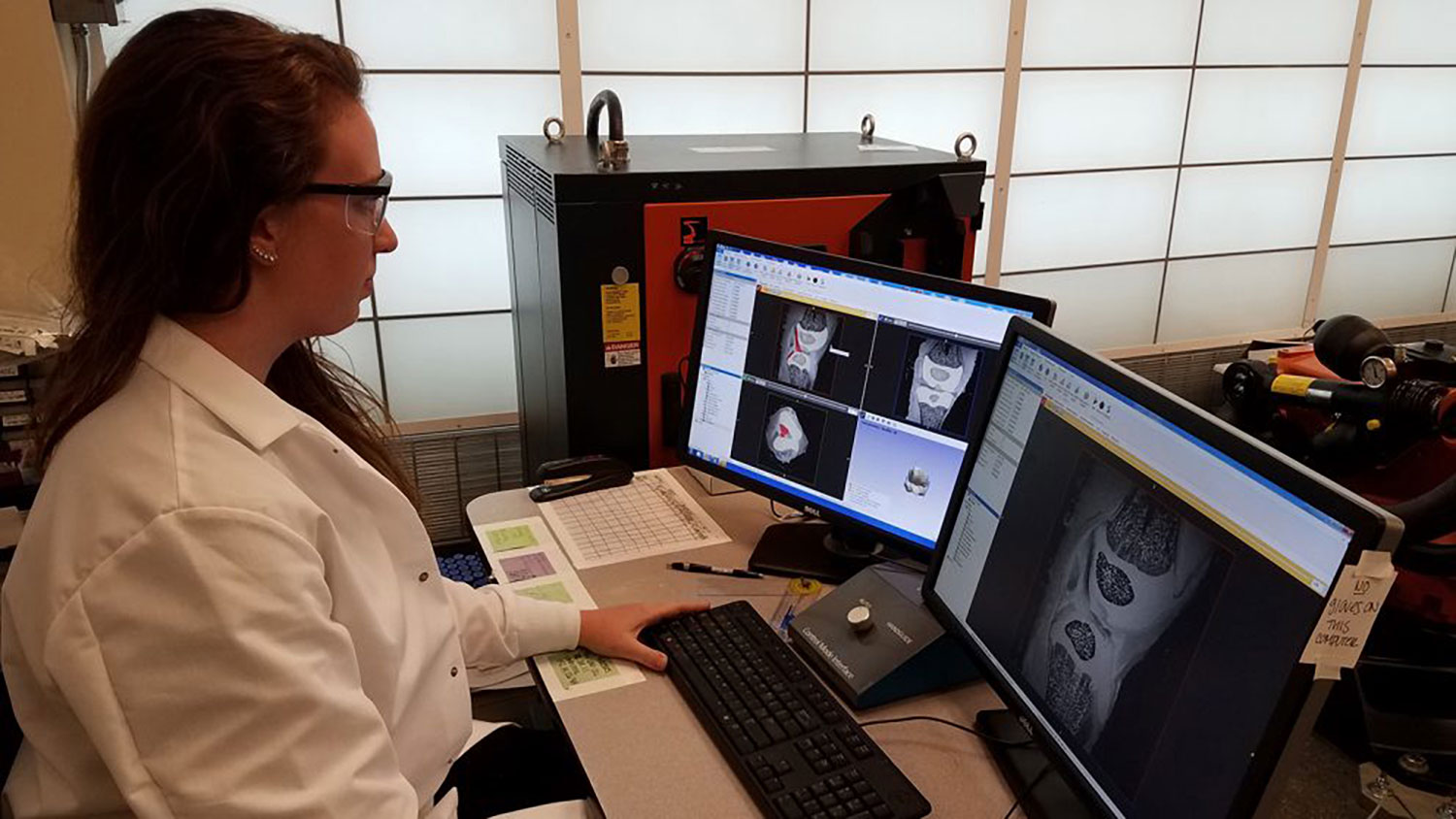

“We focused on how the orientation of knee ligaments changes over time,” says Stephanie Cone, lead author of the paper and a Ph.D. student in BME. “We found that the transitions in ligament orientation we saw in pig knees at various stages of maturity mapped very closely to the existing research on humans at comparable stages of maturity.”

“We’re excited about the potential for this model, but tracking ligament orientation using MRIs is really only a starting point,” Fisher says. “Our next steps include testing the pig knees mechanically in order to help us better understand how they move at various stages of growth: which joint components bear load, how these elements interact, and so on. A number of things change as we mature, but we are still trying to clarify the details — and those details can eventually inform future clinical practice. In fact, surgeons can use the pig model to test new surgical approaches for children and adolescents.”

Return to contents or download the Fall/Winter 2017 NC State Engineering magazine (PDF, 6.8MB).

- Categories: