Beyond the classroom

Advances in driverless cars, stories about computers learning to best mankind in games of skill and the prospect of a computer posing as a human handling your next online customer service experience have brought fresh recognition to the field of artificial intelligence (AI).

An important acknowledgement of the work done by researchers who are using AI in the field of education came in the National Academy of Engineering’s list of Grand Challenges facing humanity in the 21st century. That list recognizes the need to advance personalized learning.

Because of time and money constraints that mean a single instructor has traditionally taught a group of students, education often takes a one-size-fits-all approach. But students learn in different ways, and thanks to technology, teaching can be customized to fit their individual strengths in ways never before dreamed possible.

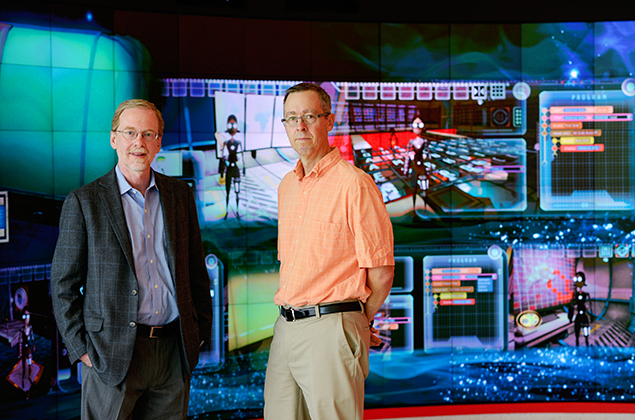

“People in my field have been working on this problem since 1970,” said Dr. James Lester, Distinguished Professor of Computer Science and director of the Center for Educational Informatics (CEI). “It was gratifying to get official recognition that this is a critical endeavor.”

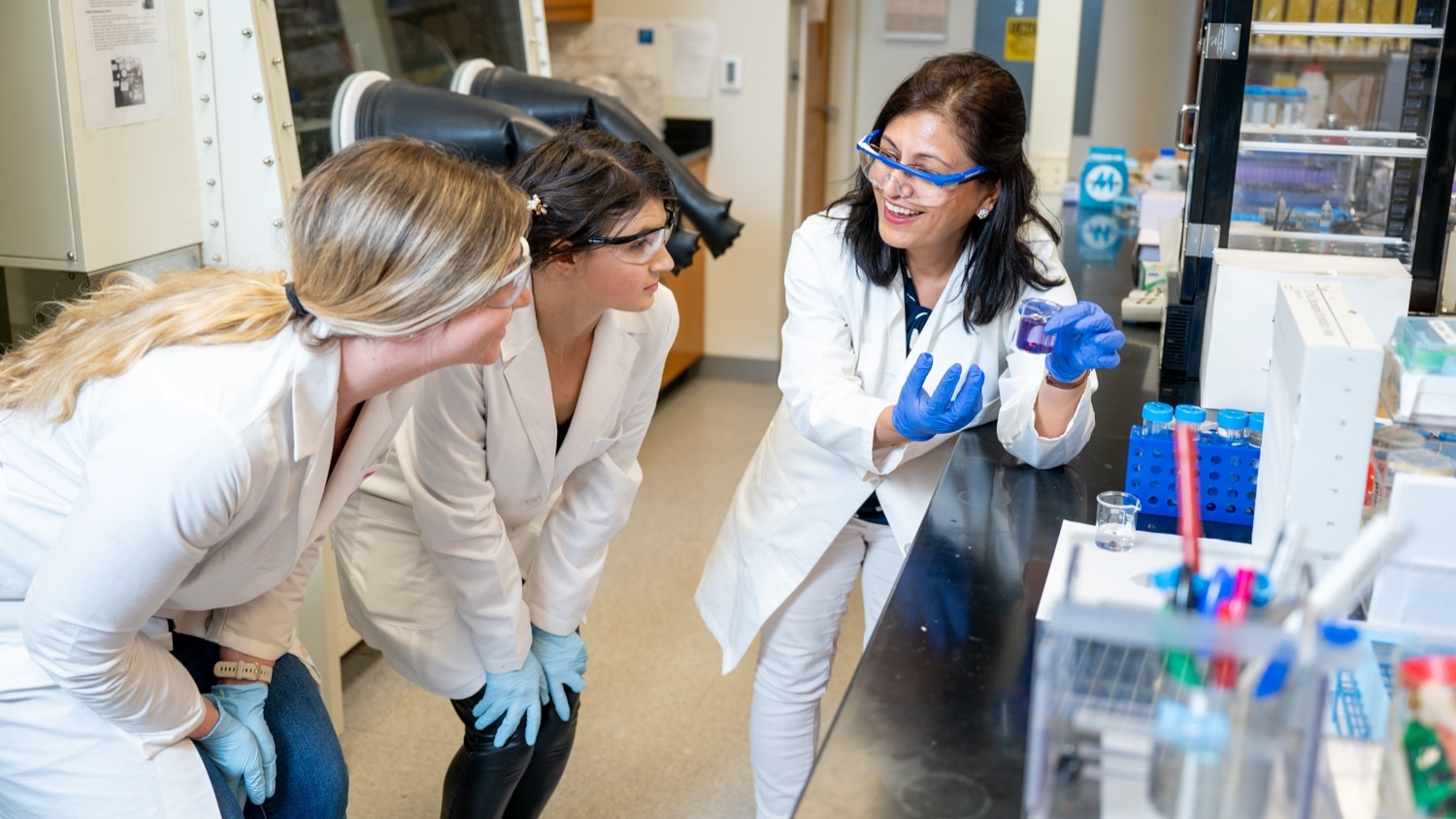

Housed in Engineering Building III on NC State’s Centennial Campus, CEI conducts research on advanced learning technologies such as educational games or intelligent tutoring systems and works to develop and disseminate them. The center has a focus on STEM education for K-12 students and undergraduates, and on computer science education, but it is broadening its scope to include other types of learning and even the field of healthcare.

Housed in Engineering Building III on NC State’s Centennial Campus, CEI conducts research on advanced learning technologies such as educational games or intelligent tutoring systems and works to develop and disseminate them. The center has a focus on STEM education for K-12 students and undergraduates, and on computer science education, but it is broadening its scope to include other types of learning and even the field of healthcare.

Led by faculty members from the Department of Computer Science who specialize in AI, the multidisciplinary center includes research scientists, game developers and digital artists.

Most research on education technology is conducted in colleges of education by teams of curriculum instruction specialists, instructional design specialists, science education specialists and educational psychologists, Lester said.

“We’re one of the very few places in the country, in the world actually, that investigates advanced learning technologies and is housed in a college of engineering.”

A teacher that scales

Lester cites what he calls “an enormous body of evidence” showing that the best educational outcomes come from one-on-one interaction between a human tutor and a human learner.

Lester cites what he calls “an enormous body of evidence” showing that the best educational outcomes come from one-on-one interaction between a human tutor and a human learner.

“That’s a marvelous thing, but unfortunately it’s completely unscaleable.”

But software is, and education is an area in which AI technologies can have a significant societal impact by creating experiences that are effective and engaging. Students supplementing their learning with AI systems learn more deeply, exhibit greater learning gains and can transfer what they learn to new problems.

The research that underpins these systems touches on the language that humans use when they teach one another, the role that narrative naturally plays in learning and how a virtual human tutor should interact with a learner.

Much of that research starts with educational data mining — finding out as much as possible about how students learn, whether in a traditional classroom, as part of an online course or by working on their own with educational technology. In some cases, it means intensive study of how a student is reacting with measures of posture, body temperature and heart rate and lots of video.

That data informs how the technologies CEI develops come together. In order to build robust systems that proactively customize the learning environment, this data must go beyond what students learn to include how they learn it.

“Educational informatics can make this happen,” said Dr. Min Chi, assistant professor of computer science. “Using the traditional paper-based tests to assess student knowledge has many drawbacks; through educational data mining we can look at how students are interacting with the system and whether they are making the ‘good choices’ during the process.”

“Educational informatics can make this happen,” said Dr. Min Chi, assistant professor of computer science. “Using the traditional paper-based tests to assess student knowledge has many drawbacks; through educational data mining we can look at how students are interacting with the system and whether they are making the ‘good choices’ during the process.”

Dr. Collin Lynch, an assistant professor of computer science, is studying how students in massive open online courses and blended courses use online tools. What conclusions about outcomes can be drawn by how often students log into the system and how long they stay there? Can that information be used in a system that would let the instructor know when a student hasn’t logged into the system for a while or would give students reminders?

When Dr. Tiffany Barnes, an associate professor of computer science, studied how her students reacted when confronted with homework assignments they didn’t understand, she assumed that the students would simply give up. That wasn’t the case; they kept trying, spinning their wheels without a way to get past the roadblock.

By using software, which includes a trace of what other students have done with the same problems in the past, Barnes and her colleagues build digital maps of how students have solved these open-ended problems in the past and give hints when a student working alone gets stuck. She likens it to using Google’s popular Maps tool.

“You’re on a journey and not only does Google Maps have the map, knowing where you start and where you go, it also knows where everyone else has gone and how other people made that journey,” Barnes said. “It can tell you where to turn next, and that’s exactly the kind of hint we generate.”

From middle school to West Point

CEI has developed game-based learning environments for middle grade students that teach science and literacy and introduce computer science concepts. At the opposite end of the spectrum, one of the center’s projects is building a similar program for cadets at the United States Military Academy.

“It’s a lot more high-stress, it’s a little more real-world,” Lester said. “But the technologies can support the learning experiences for the cadets and the students in a middle school science classroom. Many of the same problems and solutions are useful.”

Lynch has worked on intelligent systems that teach physics and is now building a system that helps students improve their written and oral argumentation skills by using software that breaks out hypotheses, claims and citations in a diagram structure that is easier to grasp than a linear form.

The center also sees a growing opportunity in healthcare, where intelligent systems can be used to educate patients. A National Science Foundation-supported project with Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco is building an interactive narrative experience that will teach adolescents about the risks of alcohol. Chi is involved in a collaborative project with a colleague in the Edward P. Fitts Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering that mines data from emergency room visits in hopes of predicting which patients will develop sepsis.

No matter the student targeted, or the subject matter covered, the system must model a learner’s knowledge, plans, goals and beliefs and intervene at the right time with customized hints, advice and feedback to maximize learning.

Help for educators

A sharp teacher can tell when her students are confused, frustrated or bored, when she needs to double back on the course material to get everyone on the same page or plow ahead.

It’s harder for a machine to do that.

Part of the center’s research looks at affect — teaching machines to recognize and understand students’ reactions and make adjustments.

So will technology one day replace human teachers? Faculty members in the CEI don’t think so. They see these technologies as a way to help solve the fact that there are too many students who need individual attention and not enough experienced human teachers to go around — that problem of scale that Lester mentions.

Chi sees educational technology as a helpful supplement for learners who are behind in class or are ahead and want to learn even more. Some students, she said, just like to learn on their own.

In addition to building data-driven systems, Barnes works to ensure that there are new teachers learning to teach computer science – and as they and their students learn about computation, they will be more comfortable using educational technologies as they will become creators.

Lester describes a scenario in which students work individually with a customized learning system, then attend a class with a strong teacher equipped with a dashboard that shows what the students have accomplished on their own.

One of the center’s research projects in partnership with Concord Consortium, a nonprofit educational technology laboratory in Massachusetts, is examining how to provide these customizable learning tools to students while also supporting teachers in the classroom.

“Technologies are fabulous,” Lester said. “They are changing people’s lives. Kids 10 years from now are going to learn very differently than they learn now. But the question is how can you leverage the capabilities of the teacher that are well beyond anything that a piece of technology can do now.”

Return to contents or download the Fall/Winter 2016 NC State Engineering magazine (PDF, 3MB).

- Categories: